The Predictive Genomics blog series provides perspectives on the use and impact of genetic risk screening & pharmacogenomics in clinical research. Predictive Genomics is powerful capability to study disease risk and understand drug response in order to focus health care resources on improving outcomes and managing costs. To talk with our team on implementing your genetic-based initiatives, please contact us or browse our predictive genomics solutions.

The Predictive Genomics blog series provides perspectives on the use and impact of genetic risk screening & pharmacogenomics in clinical research. Predictive Genomics is powerful capability to study disease risk and understand drug response in order to focus health care resources on improving outcomes and managing costs. To talk with our team on implementing your genetic-based initiatives, please contact us or browse our predictive genomics solutions.

Predicting an individual’s risk of disease based on their genotype is one of the most appealing outcomes of genomic medicine. Individuals who have been identified as having a greater risk for a particular disease may be offered more targeted therapies, including clinical procedures, medication protocols or lifestyle changes. Improved diagnosis, prognosis and treatment may also enable better outcomes and reduced the overall costs of health care for both patients and payers.

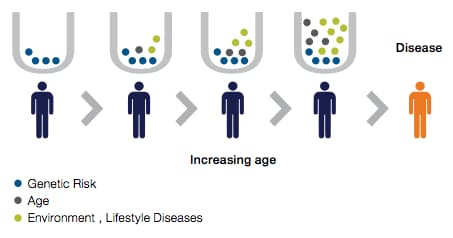

The past decade or so of genetic research has revealed that in many common complex diseases, such as some types of heart disease, cancer, diabetes and brain disorders, multiple common genetic variants of small effect may play a greater role than rare single-gene mutations. A single trait may be affected by thousands of variants throughout the genome. Although one variant among thousands might not be very useful in predicting complex traits, quantifying the cumulative effects of very large set of variants into a single metric, or polygenic risk score (PRS), may overcome this challenge.

A PRS is calculated from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) by totaling the number of risk-associated alleles carried by an individual and weighting them according to the magnitude of their effect. Researchers have been attempting to develop PRSs since the early days of GWAS. However, initial efforts were hampered by three challenges: 1) small GWASs limited the precision of estimations of risk contribution for individual variants; 2) computational risk-scoring methods were limited; and 3) data sets large enough to verify and test the PRSs were also limited [1].

New studies validate PRSs

The capabilities of GWAS have made great progress since those early days. Several major developments are driving new studies and expectations for the use of a PRS as a clinical tool. The increasing numbers of biobanks that provide rich phenotypic and genetic data enable researchers to assemble the very large longitudinal cohorts that are needed to verify and test PRSs. Researchers now have access to thousands of GWASs, some including as many as one million subjects. New methods have also been developed to compute PRSs.

For example, a team from Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the Broad Institute [1] has recently developed and verified genome-wide PRSs for five common diseases: coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease and breast cancer. Over 400,000 individuals in the UK Biobank were genotyped using either the Applied Biosystems™ UK BiLEVE Axiom™ Array or the UK Biobank Axiom™ Array, each consisting of over 800,000 genetic markers scattered across the genome. Additional genotypes were imputed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium resource, the UK10K panel and the 1000 Genomes Project panel. This approach resulted in statistically significant percentages of the population showing greater than three-fold increased risk for these diseases. The scores were verified and tested within the UK Biobank population.

A second recent global initiative [2] brought together almost 170,000 subjects from 69 studies to dig deeper into risk scoring for breast cancer by developing a methodology to enable the stratification of breast cancer subtypes. The PRSs they developed were verified empirically in 10 prospective studies with a cohort of 20,000 independent test subjects and 190,000 subjects from the UK Biobank. The UK Biobank samples were genotyped using the UK BiLEVE Axiom array and UK Biobank Axiom array, and imputed to the 1000 Genomes Project and UK10K reference panels. This study yielded PRSs to predict ER-specific breast cancer that were also optimized to predict subtype-specific disease.

Important considerations

There is tremendous excitement surrounding PRS; however, we must be cautious in its application and consider several issues.

- Other underlying mechanisms may contribute to a PRS. For some diseases, the genetic component may not be the most influential factor. For example, an obese person may have a low PRS but may need greater diabetes prevention efforts than a thin person with a high PRS. It is also well-known that factors such as family history, socioeconomic and physical environments, and lifestyle impact disease risk. Different diseases will have different scoring factors. How should the genetic contributors of risk stratification be integrated with these and any other risk factors? Biobanks that focus on individuals with other common factors, such as a shared experience as noted below, will be instrumental in answering these questions.For example, the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (ToMMo) is gathering genetic and biospecimen data from individuals in the Tohoku region of Japan to study the health consequences of the devastating 2011 earthquake. The Million Veteran Program is creating a biobank only from individuals who have served in the US military, specifically for the study of military-related and other diseases.

- Clinicians use a variety of methods, tools and metrics for disease diagnosis and prognosis, including pathology, imaging, blood testing and patient observation. Genetic information is a powerful new addition to the diagnostic toolbox, but it does not replace any of the other tools. How can PRSs be integrated with other clinical metrics?

- Much of the genotyping data, cohorts and variant panels available to date have been developed and tested in people of primarily European descent. However, many diseases have different impacts or prevalence in different populations. For example, African-Americans have a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease than people of European descent. In this case, PRSs developed using cohorts and variants from European populations may be skewed for African-Americans.Population-specific biobanks such as the China Kadoorie Biobank and the FinnGen study, as well as arrays such as the Applied Biosystems™ Axiom™ GenomeWide Population-Optimized Arrays, will be vital in determining population-based variations and ensuring risk stratification equity across ethnic groups and other population segments.

- Clinical application of PRSs will also lead to very challenging ethical questions. Although it may be possible to determine a PRS in an individual well before any indication arises, other considerations may make it inappropriate or even harmful for either the patient or the clinician to have that knowledge. Consider, for example, conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, for which there is currently no effective treatment or cure, compared to heart disease, for which there may be multiple screening, clinical and lifestyle options that could significantly minimize risk. Even when early detection or prevention is possible, health care providers may have limited resources to address all affected individuals. Providers may have to prioritize resources for individuals with different levels of risk. How or when should PRS data be offered to patients with potential risk?

Conclusion

As the first studies that reveal verified PRSs are published, anticipation grows for the potential contribution of PRS for disease diagnosis, prognosis and treatment in the era of precision medicine. But the excitement is also tempered by the considerations of other disease factors, additional diagnostic approaches, sample bias and ethical concerns. Ongoing growth in the scope and scale of GWASs and biobank resources, along with advances in computational methodologies, are enabling faster development and stronger statistical verification of new PRS approaches that will help to determine the future of this promising tool.

For information on genotyping strategies adopted by other researchers, go to thermofisher.com/scientistspotlight

For research use only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures.

Have a question for our technical specialists? Contact us at thermofisher.com/genotyping-microarray-contact

References

1. Khera, A.V., et al. (2018) “Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations,” Nat Genet 50: 1219–1224.

2. Mavaddat, N., et al. (2019) “Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes,” Am J Hum Genet 104: 21–34.

I would like to apply statistical analysis on polygenic risk. I am a statistician by trade and I am interested in genomic medicine. I would be glad to receive secondary data that will enable me carry out further research.Thanks in anticipation

hy

It will be good but can u help me one thing

anticipation grows for the potential

contribution of PRS for disease diagnosis, prognosis and

treatment in the era of precision medicine. But the

excitement is also tempered by the considerations of

other disease factors, additional diagnostic approaches,

sample bias and ethical concerns.I love this post

53 pm

anticipation grows

for the potential

contribution of PRS

for disease

diagnosis, prognosis

and

treatment in the

era of precision

medicine. But the

excitement is also

tempered by the

considerations of

other disease

factors, additional

diagnostic

approaches,

sample bias and

ethical concerns.I

love this post

Reply

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be

published. Required fields are

marked *

Comment

Name *

Email *

Website

Post Comment

Privacy Statement Te

Bonsoir, je m appelle Saidi Awazi suis étudiant en Informatique…

Je voulais juste vous demander un pdf a jour sur le cours de html-css …

Merci et Bne soirée

Good job and am Interesting in it.!!!

You are solving problems in a wonderful way