The Predictive Genomics blog series provides perspectives on the use and impact of genomics in clinical care for health systems, national initiatives and researchers. Topics focus on the role of genetics, genetic risk screening, pharmacogenomics, and the importance of diversity in genomic databases. To talk with our team on implementing your genetic-based initiatives, please contact us or browse our predictive genomic solutions.

The Predictive Genomics blog series provides perspectives on the use and impact of genomics in clinical care for health systems, national initiatives and researchers. Topics focus on the role of genetics, genetic risk screening, pharmacogenomics, and the importance of diversity in genomic databases. To talk with our team on implementing your genetic-based initiatives, please contact us or browse our predictive genomic solutions.

Several different types of information could be reported to participants in genomics-based screening programs. The options can be broken down into a few categories: rare diseases, common diseases, pharmacogenetics, and non-clinical traits and genetic ancestry.

Rare inherited diseases might affect the participant themselves (autosomal dominant) or might not affect the participant, but could affect their offspring (autosomal recessive). Examples of these types are Lynch syndrome and cystic fibrosis, respectively. The risk for common complex diseases, such as diabetes or heart disease, may be assessed by polygenic risk scores that combine the effects of multiple low-impact variants. Pharmacogenetics does not detect disease presence or risk, but it captures variation in the way humans process drugs. Traits and ancestry do not have direct medical implications. Each of these categories has pros and cons when considering their inclusion in a genomics-based screening program. Genomics-based screening is not currently recommended for routine clinical use, but results may be returned to participants as part of an IRB-approved research study.

Rare Genetic Diseases

Screening for rare inherited diseases could detect preventable conditions that might otherwise go undetected until symptoms manifest. This allows care providers the opportunity to suggest increased monitoring or interventions to prevent or detect disease earlier. However, depending on the genes included in the screening, the natural history of disease in a healthy population is unknown at this time. Without this information, a health economic model cannot be constructed and there is no clear return on investment. Depending on the gene set, 1-2% of individuals tested will get a positive result.

Testing asymptomatic individuals for unsuspected conditions is not new to the medical and public health communities. The principles of screening and test design strategy are well established in medical literature (Dobrow et al., 2018; Takwoingi and Quinn, 2018). First published in 1968 by the World Health Organization (WHO; Wilson, Jungner, and World Health Organization, 1968), these principles were adapted to DNA-based preventive screening in 2003 (Khoury, McCabe, and McCabe, 2003). Candidate conditions for screening should include a well-understood natural history, established prevalence, a clinical confirmatory test to identify false positives, and safe, effective, and accessible management actions. The test itself must have well-defined performance metrics, including predictive values, and must be optimized for individuals with a low prior probability of disease.

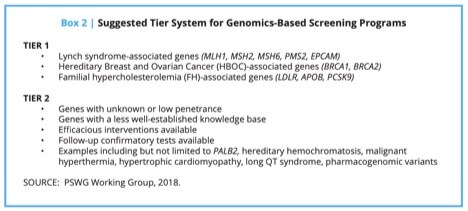

Two common gene lists are often used for returning results in genomic-based screening programs: CDC Tier 1 and the ACMG59™. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has issued recommendations for reporting secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing in which they enumerate 27 conditions (59 genes) for inclusion in an opportunistic screen. However, for the ACMG 59TM conditions, the prevalence and penetrance in an unselected population are mostly unknown. In fact, recent studies have shown that several of these conditions appear to have a very low penetrance in an unselected population (Haggerty et al., 2017; Rocha, Schwiter, Hallquist, and Buchanan, n.d.). The ACMG has recently re-emphasized that this set of genes is not appropriate for general screening until their natural history and epidemiology are better understood (ACMG Board of Directors, 2019).

In 2018, the Genomics and Population Health Action Collaborative, an ad hoc activity of the Roundtable on Genomics and Precision Health of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published A Proposed Approach for Implementing Genomics-Based Screening Programs for Healthy Adults. The paper addresses the optimal genes to include in genomics-based screening programs, the complexity of identifying a point in time at which to begin screening, who should perform the screening, where the programs should be administered, and ethical and economic considerations.

The working group focused on well-studied genes (and well-characterized alleles within them) linked to conditions with well-studied, effective clinical interventions for the purpose of primary screening in the general population. Such an approach will allow for provisionally implementing and investigating a targeted version of genomic screening that stands the best chance of offering a high ratio of benefit to harm in the general population. In developing a list of potential genes for population screening, the group considered the existing difficulties inherent in variant assessment, the risk of false positive results, and the potential for over-diagnosis given the low prior probability that those screened actually have a disease. The lower the prevalence of disease in the test population, the lower the positive predictive value of the test.

“Tier 1” consists of those genes with high penetrance (the probability that disease will appear when a disease-related genotype is present), well-understood links to disease, and well-established, effective interventions that result in the substantial prevention or mitigation of disease or disease risk. The three conditions in the CDC’s Office of Public Health Genomics (OPHG) Tier 1 Genomics Applications were fully in line with the screening criteria. These are Lynch syndrome, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and familial hypercholesterolemia.

“Tier 2” consists of those genes that could be possible candidates for screening, but there may be disagreement about whether there is sufficient evidence for population screening. Although there are no definitive and universally agreed-upon criteria that qualify a gene as a candidate for screening, it should be emphasized that a strong justification regarding specific actionability should be present. Tier 2 genes should be “close calls.”

As mentioned, these conditions are very rare in the general population. To minimize false positives, screening results should be interpreted more stringently when testing the general population compared to testing the same genes in a higher-risk population, such as those in a medical genetics specialty clinic (Hagenkord et al., 2020). In addition, genetic tests, regardless of the technology platform, have variable breadth of coverage and residual risk. It is important that physicians and patient participants understand the residual risk (Lu et al., 2019).

Regardless of the gene set used, it is important for the program to track clinical outcomes. This real-world evidence can assess how beneficial (or possibly harmful) the screening program is when actually implemented in the study setting.

Polygenic Risk Scores (PRSs)

Common chronic diseases include diabetes, heart disease and cancer. They have complex, multifactorial etiologies that involve the interplay of both genetic susceptibility and environmental risk factors, which are broadly defined as lifestyle, behavioral, occupational or environmental exposures, and other health conditions. This type of result is theoretically applicable to all participants. In practice, however, the clinical validity and utility of PRSs tend to apply only to the extreme ends of polygenic risk—very high- or very low-risk individuals. Torkamani et al. (2018) recently reviewed PRSs and categorized their potential utility into three major classes of interventions:

- PRS-informed therapeutic intervention (the part that PRS can play in the selection of interventions to treat or prevent disease)

- PRS-informed disease screening (the role that PRS can have in the decision to initiate and the interpretation of disease screens)

- PRS-informed life planning (the personal utility that PRSs can provide, even in the absence of preventive actions).

In general, the clinical utility of a risk model largely depends on its ability to stratify a population into categories with sufficiently distinct risks to substantially affect the risk–benefit balance of public health or clinical interventions. Implementation of PRS in a large population under a research protocol provides an excellent opportunity to better understand the clinical utility of specific claims based on PRSs.

Barriers to clinical implementation, outside a research protocol, are covered in a separate blog post titled “What Needs to Happen for PRS to Be Routinely Used in Health Care.” Briefly, those barriers include:

- Studies for each specific intended use must demonstrate analytical validity, clinical validity and, ultimately, clinical utility and health economic benefits.

- Unlike typical biomarker-based clinical tests, PRSs are models built from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and require additional steps in model development and validation.

- Replicability and comparability studies of PRS predictions are needed to ensure that the model behaves as expected in the test population, not just the population that was used to build the model. This means that many PRSs may only be applicable to participants of Northern European descent, which raises diversity and inclusion concerns.

Depending on the clinical claim being made, participants may find the results interesting and engaging. Large-scale research studies that return PRSs can help establish the validity and utility of specific claims in your local participant population and can lead to the development of practice standards that enable physicians to confidently act on the results.

Pharmacogenetics

Genetic variations of certain genes do not cause a disease or increase disease risk, but they may influence how an individual metabolizes certain drugs. Pharmacogenomics (PGx) is the application of genetic testing to guide drug selection and/or dosing. The Clinical Pharmacogenomic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) provides guidelines of how to select or dose medications based on pharmacogenomic variants. The organization also rates the strength and robustness of evidence underlying drug-gene interactions and the clinical utility of use within affected populations. Well-known examples include the dosing of certain cardiovascular drugs (e.g., Clopidogrel) or antidepressants.

Several programs have provided pro-active pharmacogenetic testing, including Vanderbilt’s PREDICT, Inova’s MediMap, and several commercial entities. The NIH-sponsored All of Us program also plans to return pharmacogenetic results to participants. Large-scale collaborative research studies on the clinical validity and utility of pharmacogenetics are ongoing, such as the EMERGE-PGx program. Given the potential to increase efficacy, reduce toxicity and tailor optimal dosing, patient-participants appear to have a high level of interest in receiving pharmacogenetic results.

Consumer Interest in Pharmacogenetics (Bousman et al., 2017)

- A US survey of public attitudes toward pharmacogenetic testing suggested the majority (>73%) of people are interested in pharmacogenetic testing to assist with drug selection, guide dosing and/or predict side effects.

- A survey of 910 undergraduate medicine and science students showed 90% were in favor of pharmacogenetic testing.

- A telephone survey of US adults reported younger Caucasians with a college education and a history of side effects from medication were more likely to be interested in testing, but most (73%) respondents would not agree to pharmacogenetic testing if there was a risk that their genetic material or information would be shared without their permission.

In addition, returning pharmacogenetic information to participants may increase their medication adherence (Dolgin, 2013; Li et al., 2014; Winner et al., 2015). Participants who underwent genotyping had an increase in their perception of the need to take a drug to prevent a disease. Genotyped participants also had an increased rate of filling their prescriptions and improved outcomes compared with non-genotyped participants. Interestingly, the benefit among genotyped participants was present in both carriers of the risk allele and non-carriers, suggesting that genetic testing, regardless of the test result, may provide benefit to participants and providers in terms of addressing concerns about perceived risk of adverse drug reactions, participating in shared decision-making and optimizing medication adherence.

Despite this high level of consumer interest and the potential for improved outcomes and compliance, there is still debate about the clinical validity of many claims included in the CPIC guidelines, as well as whether or not consumers will adjust their medications without talking to their doctors if a preemptive pharmacogenetic report is given to participants in large-scale genomic screening programs. How an individual metabolizes a drug depends partially on genetics, but it is also influenced by many factors that are not captured by a genetic test, such as diet, lifestyle, other biological influences, age, sex, comorbidities, other drugs and compliance/adherence. These factors are difficult to control for in large studies. One study suggests that the risk of independent medication adjustments is low (Carere et al., 2017), but additional studies will be needed to convince the critics that this risk is not substantial.

These concerns are reflected in the FDA’s 2018 Safety Alert. The FDA Warns Against the Use of Many Genetic Tests with Unapproved Claims to Predict Patient Response to Specific Medications: FDA Safety Communication, the agency’s active outreach to entities providing pre-emptive pharmacogenetic testing, and their subsequent warning letter to Inova Health. In response, the health system discontinued its pharmacogenetics program and other laboratories removed drug names and management recommendations from their websites and reports. This prompted the Association for Molecular Pathology to release a Position Statement: Best Practices for Clinical Pharmacogenomic Testing in 2019, which contradicts the recommendations made by the agency in their Safety Alert. In addition, the FDA required the All of Us program to submit an investigational device exemption (IDE) submission. The FDA requires sponsors to file for an exemption before an investigational device that poses significant risk to human subjects can be used in a clinical study. Large-scale genetic screening programs considering returning pharmacogenetic results to patient-participants should familiarize themselves with these actions by the agency and obtain legal advice to assure they are minimizing regulatory risk.

Traits and Ancestry

Genetics can also tell a participant about interesting traits, such as caffeine metabolism or whether or not cilantro tastes soapy, as well as genetic ancestry. Since these tests are not considered in vitro diagnostics by the FDA, there is no regulatory requirement to establish the analytical or clinical validity of these biomarkers. However, some consumers find these results interesting and engaging. It may increase participation in the program, create buzz and provide all participants with some type of “positive” result. Some health systems see these results as benefits, while others think they may cause confusion about what is medical and what is fun genetics, or tarnish a respected medical brand. Each health system or government-sponsored research program will need to consider the pros and cons of including interesting traits and ancestry.

There are important pros and cons to consider when deciding which types of results to return to participants in large-scale genomic screening studies. Regardless of which type of information is returned, it is critical that participants are cognizant of the limitations prior to participating and that the physicians who may be receiving unsolicited genetic test results are educated and supported as to which actions are appropriate or exist. Consumers tend to respond positively to the option to participate in research studies when they feel they are helping and they are rewarded with information in return. These large studies are how the genetics community will ultimately demonstrate the validity, utility and cost-effectiveness needed for clinical implementation and practice guidelines.

References:

ACMG Board of Directors. (2019) “The use of ACMG secondary findings recommendations for general population screening: A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG),” Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 21(7), pp. 1467–1468.

Bousman, C.A., Forbes, M., Jayaram, M., Eyre, H., Reynolds, C.F., Berk, M., Hopwood, M., and Ng, C. (2017) “Antidepressant prescribing in the precision medicine era: A prescriber’s primer on pharmacogenetic tools.” BMC Psychiatry, https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12888-017-1230-5.

Carere, D.A., VanderWeele, T.J., Vassy, J.L., van der Wouden, C.H., Roberts, J.S., Kraft, P., and Green, R.C. (2017) “Prescription medication changes following direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing: Findings from the Impact of Personal Genomics (PGen) study,” Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 19(5): pp. 537–545.

Dobrow, M.J., Hagens, V., Chafe, R., Sullivan, T., and Rabeneck, L. (2018) “Consolidated principles for screening based on a systematic review and consensus process,” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(14): pp. E422–E429.

Dolgin, E. (2013) “Pharmacogenetic tests yield bonus benefit: Better drug adherence,” Nature Medicine, 19(11): pp. 1354–1355.

Hagenkord, J., Funke, B., Qian, E., Hegde, M., Jacobs, K.B., Ferber, M., Lebo, M., Buchanan, A., and Bick, D. (2020) “Design and reporting considerations for genetic screening tests,” J Mol Diagn., 22(5): pp. 599–609.

Haggerty, C.M., James, C.A., Calkins, H., Tichnell, C., Leader, J.B., Hartzel, D.N., Nevius, C.D., et al. (2017) “Electronic health record phenotype in subjects with genetic variants associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: A study of 30,716 subjects with exome sequencing,” Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 19(11): pp. 1245–1252.

Khoury, M.J., McCabe, L.L., and McCabe, E.R.B. (2003) “Population screening in the age of genomic medicine,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 348(1): pp. 50–58.

Li, J.H., Joy, S.V., Haga, S.B., Orlando, L.A., Kraus, W.E., Ginsburg, G.S., and Voora, D. (2014) “Genetically guided statin therapy on statin perceptions, adherence, and cholesterol lowering: A pilot implementation study in primary care patients,” Journal of Personalized Medicine, 4(2): pp. 147–162.

Rocha, H., Schwiter, R., Hallquist, M., and Buchanan, A. (n.d.) “APC variant identification in an unselected patient population: Where are the polyps?” ACMG Annual Meeting 2019. Accessed July 16, 2019. https://acmg.expoplanner.com/index.cfm?do=expomap.sess&event_id=13&session_id=9583.

Takwoingi, Y., and Quinn, T.J. (2018) “Review of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies in older people,” Age and Ageing, 47(3): pp. 349–355.

Torkamani, A., Wineinger, N.E., and Topol, E.J. (2018) “The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores,” Nature Reviews, Genetics, 19(9): pp. 581–590.

Wilson, J.M.G., Jungner, G., and World Health Organization. (1968) “Principles and practice of screening for disease,” https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650.

Winner, J.G., Carhart, J.M., Altar, C.A., Goldfarb, S., Allen, J.D., Lavezzari, G., Parsons, K.K., Marshak, A.G., Garavaglia, S., and Dechairo, B.M. (2015) “Combinatorial pharmacogenomic guidance for psychiatric medications reduces overall pharmacy costs in a 1-year prospective evaluation,” Current Medical Research and Opinion, 31(9): pp. 1633–1643.

Leave a Reply